What running shoes and a hundred-year-old mouse have in common

Two weeks ago, a post from Massimo Giunco, a 21-year Nike marketing veteran who left in 2022 went viral. The post is absolutely eviscerating of Nike and it’s turned-around strategy, which began around four years ago with the installation of a new CEO, John Donahoe.

If you haven’t read the post, do so now. It’s a treasure trove of takes from inside one of the most famous brands in the world, and is a true tale of tragic decline that feels completely avoidable and not-at-all inevitable.

What’s wild about this saga, though, is that Giunco’s line-by-line takedown of Nike’s new strategy is not new news. It goes like this (warning – jargon incoming – but I’ll explain it later):

- Brand has been built on decades of building mental and physical availability

- Brand is well-known, well-loved and – crucially - well bought because mental and physical availability are high

- Brand thinks they can create efficiencies by reducing investment in mental and/or physical availability – they’ve built their castle, now they can live in it

- Relatedly, but differently, Brand overplays its relationship with customers and position in the world and… tries to go direct-to-customer (DTC) instead: they create their own store, marketplace or app where their offering is exclusively available, to solve this efficiency “problem”

- Which leads a loss in both physical and mental availability, because:

- Customers have to learn a new place to go for Brand, if they bother going at all (habits are hard to change)

- Customers can only go to one location to buy many things from Brand, so marketing money is shifted away from activity that increases awareness of an affinity for Brand, and towards convincing people to go to the DTC offer, often with deep discounts rather than price premiums

- Which… leads to a loss in sales for Brand

And this is exactly what happened with Nike. The incoming CEO bet the house on Nike.com for sales and marketing. Building a direct relationship with customers. Losing focus on product development and brand storytelling.

It’s tempting. But building your own marketing technology stack that lets you “own your customer” and measure everything down to the tiniest details does not equal effectiveness. In Giunco’s words:

Nike invested a material amount of dollars (billions) into something that was less effective but easier to be measured vs something that was more effective but less easy to be measured. In conclusion: an impressive waste of money.

Implicit in this is that investing in brand activities (Giunco calls it “demand creation”, which I think is a great way to think about it) and product development is a better use of budget versus building direct-to-consumer activities. Is this true though? Isn’t everyone doing trying to build their own DTC offer these days? Surely if they continue to invest, then it works?

Well, yes and no. It’s complicated. Both direct sales and brand activities are important. This has ebbed and flowed over time: in the late 2000s and early 2010s, performance marketing on Facebook with immediate costs of acquisition and lifetime value predictions were addictive. Brands could see, in real-time, how much “marketing” cost them. And then they’d dial up that sure-fire, actual cost, depending on their goals. DTC is the same.

But the problem is, this isn’t marketing, not in the truest sense of the word. It’s activation. It’s functional messaging to get people who are ready to buy over the line. It’s not an investment in getting customers to know who you are or remember you or see you and choose you.

If they went the opposite way, though, and only focused on brand or product-led awareness or favourability driving activities, then they’d never have a call-to-action for the customer and never sell anything as a result.

Balance. Well, as we’ll see, not equally balanced. But balance.

Nike has gone too far one way – all the way – to Nike.com. This was bad for business. Let’s have a little look today at the theory behind Giunco’s post.

You’ll see a little later, too, that Nike isn’t the only one To be tempted by the DTC dream.

Making it a no-brainer

In 2010, Byron Sharp, a professor of marketing science and Director at the famed Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science published a book called “How Brands Grow”.

In it, he argues that marketing theory has not traditionally been based on actual data or science: that is, the frameworks and methods that marketers have been taught for decades are – to heavily paraphrase – bullshit. The evidence tells him that the key to brand growth is two-pronged, actually: (a) build mental availability and (b) build physical availability. By this, he means making a brand as easy as possible to remember and buy in all situations.

A few years later, Peter Field and Les Binet published The Long and the Short of It, which builds on Sharp’s evidence-based approach, and then some.

Not only do they agree that the key to brand growth is making it easy to buy in all situations, but they observe a general trend: that marketers are obsessed with immediate data to a fault, that they are running sales activation and performance marketing tactics like Facebook ads that give a direct return on investment number quickly and easily, and everyone’s saying that traditional marketing activities just aren’t important anymore.

Their research, based on a study of over 700 brands, found that an over-focus on these tactics is value destructive to brands, and there is a universally applicable law that says you’ve got to do brand marketing and sales marketing to grow a brand. Even if you can’t measure the former immediately, over time the effects will appear and your brand will grow. And the latter will drive immediate sales, which you can reinvest into your product and your brand.

So marketing strategy should be easy, right? It all boils down to make it easy for a customer to buy your brand. That might mean that you have to be in every single grocery shop (think Coca Cola). It might mean you have to spend tens of millions of pounds a year reminding consumers you exist (think… Coca Cola). It might mean you need to surprise or shock people sometimes (are you thinking Coca Cola? This one’s probably more Red Bull).

The point is, growth comes from human brains taking human actions and your strategy should be aimed at that, at influencing that behaviour online and in shops and on TV and everywhere humans are.

This is where Nike went wrong. And it’s where Disney almost went wrong, too.

Disney minus

In 2019, Disney launched Disney+, its direct to consumer play. At the time, CEO Bob Iger was bullish:

“The teams who’ve engaged with it here feel really good about where we are,” said Iger. “To use the word ‘excited’ would probably be an understatement.”

— Iger on the Disney+ launch, according to Forbes.

This feels easy to follow: Disney is a great brand, why not cut out the middleman and subscribe directly to get your favour Disney classics or the new Marvel movie?

But this only works if you continue investing in what makes the brand great – by reminding customers why your brand (or in Disney’s case today, house of brands – from Marvel to Star Wars to Pixar) is magical or thrilling or fantastical or fun with great products and great advertising, and by creating those experiences in the first place.

Unfortunately, Disney’s direction faltered here. Bob Iger left the company soon after the Disney+ launch and his successor – another Bob – took the company on a path that prioritised direct sales to and deep discounts for Disney+ in order to drive quick growth to it.

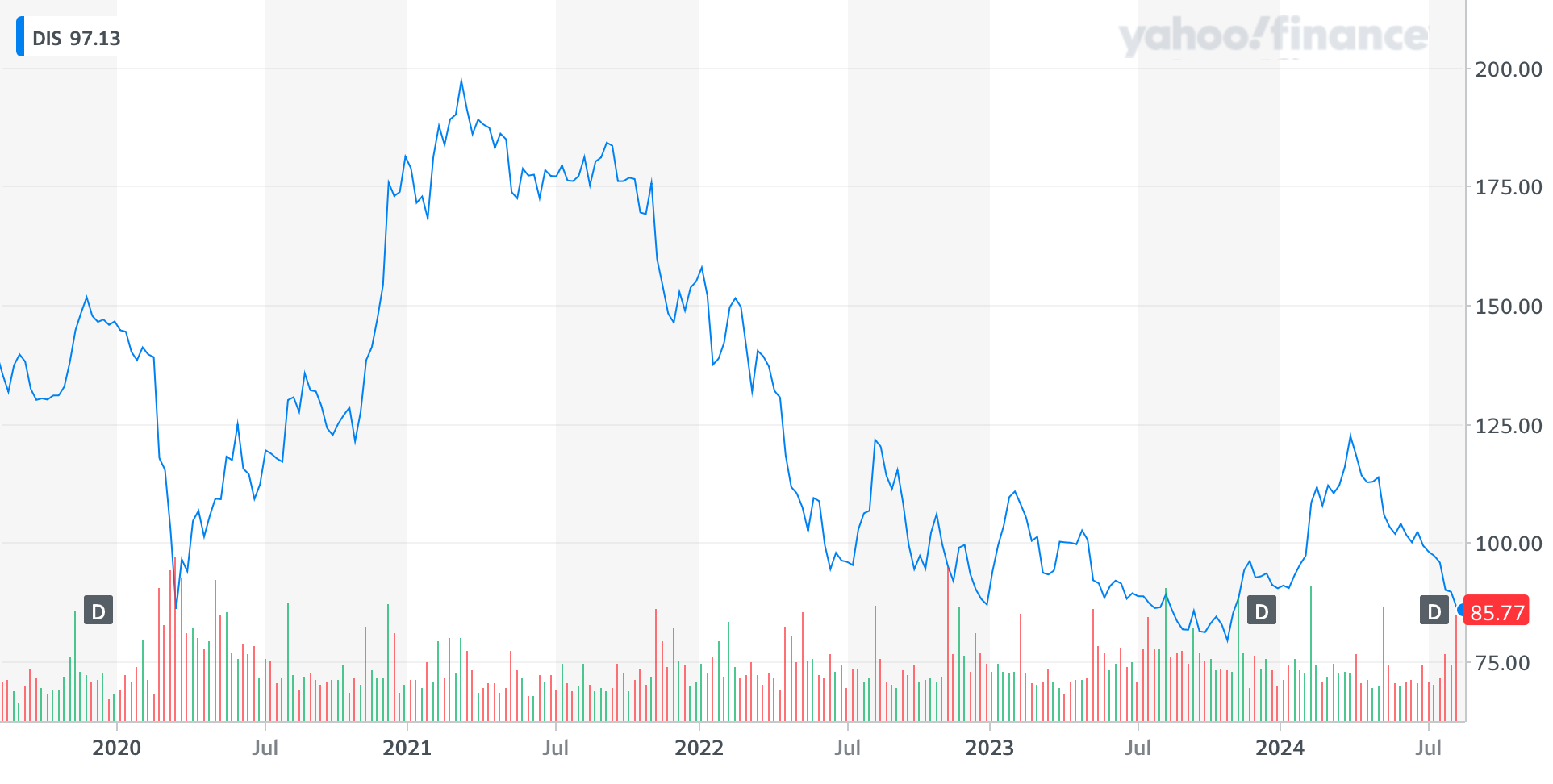

Disney advertising stopped showing off the next big blockbuster and started offering Disney+ for 6 months at a reduced cost. They prioritised a flood of content to fill Disney+ hours rather than producing really great stuff that’ll delight customers. Cost-cutting began at the Disney Parks. They lost their sparkle because they prioritised their DTC offering over everything else. Their share price fell. As we were all emerging from the COVID pandemic in 2022, look what happened:

After that great fall, Iger returned to the company and brought back a focus on what makes Disney great – magical customer experiences and great content. Disney+ became a channel, not the channel, for Disney content. They haven’t recovered yet, but their strategy has been righted.

Fewer films sent to the cinema first as marquee marketing moments. Then eventually to Disney+, having driven demand in the cinema and sparking word of mouth recommendations. Big brand advertising that focused on Disney’s storytelling, not their app.

Iger and co also started selling their old, good, films and TV shows to free-to-air broadcasters to drive mental and physical availability, which pays off with visits to Disneyland, but is also an immediate revenue driver from channels who are increasingly looking to fill schedules and streaming services.

So the direct-to-consumer offering is relegated to a chess piece, rather than being the whole board. Disney focuses on creating great products (content and experiences) and driving awareness for them (tentpole cinema releases, billboards advertising content, rather than the service).

It’ll take time, but I think that chart up there will start to grow up and to the right soon.

Over-importance

Nike and Disney are among the most recognised brands in the world. They’re huge companies, with huge companies and huge valuations. How are they falling for the temptation of overly-measured data and customer relationship management over demand creation and creating brand love to drive sales?

I think the answer is that brands over-estimate their place in peoples’ lives. In truth, brand managers and CMOs spend so much more time thinking about brands than consumers do.

Customers have jobs to be done, and they have brands that do those jobs for them. If I’m training for a marathon, a job a brand might do for me is to support my feet with comfortable running shoes. That’s when I think about Nike.

Yet when I went to Runner’s Need to try out some shoes, not only were there very few in the shop (physical availability), I didn’t ask about them, nor did the salesperson talk about them, probably because Nike hasn’t been memorable or distinctive or desirable over the last few years (mental availability).

I don’t think about Nike when I’m not in a buying situation, unless they make me aware by getting my attention with great advertising (on TV) on by integrating into moments I’d otherwise not be thinking of them (on football shirts). And if they're not stocked in Runner's Need, then that's a lost sale.

The same job-to-be-done dynamic is true of Disney. I turn on my TV and I look for something I've heard about or a friend has recommended. If Disney's not investing in great shows or reminding me that they make good shows, I'm not going to start with opening the Disney+ app. Maybe I'll go to Apple TV+ instead. That's why marketing Disney+, rather than the content on Disney+, was a big misstep four years ago.

Great brands are at great risk of taking their product and brand building competencies for granted. But it’s also a sense of entitlement and importance: as if the brand will always be as it is without investment in its soul.

So when times are good and their castles are built, they turn to efficiencies – and direct-to-consumer (where they don't have one) becomes attractive. But this, as we've seen, comes with costs if you don't continue to invest in your great product and your great brand.

Disney is coming out of their slump, I think.

Nike has a long way to go.