Four ways marketers can beat electric car inertia

What app-based banks and electric cars have in common.

Two months ago, I got a new car. It’s a bright orange MG4 and I love it.

It's electric.

I was pretty blown away by two things that happened once we’d got the car.

The first – how fun the car feels to drive and how easy and convenient it is to use.

The second – how pretty much every person I’ve told about our car thinks the opposite is true.

It got me thinking. I think electric vehicles, particularly in the UK, might have a marketing problem. Because the expectation of how it’d be to own an electric car – a faff, a nightmare, can’t get anywhere on a single charge, nowhere to charge it – just absolutely does not match the reality. It has been a joy. In fact, I think it’s better than owning a petrol car.

Two caveats here, before we continue. The first – I am painfully aware that I may be exhibiting signs of choice-supportive bias – the psychological phenomenon where people rationalise purchases in retrospect with more positive associations than they otherwise would have done. I am trying my best to counteract this! But I also think it doesn’t matter to today’s post – even if I am making this situation better than it is in my own head, the point still stands, I think – electric vehicles just are not anywhere near as bad as many people think they are.

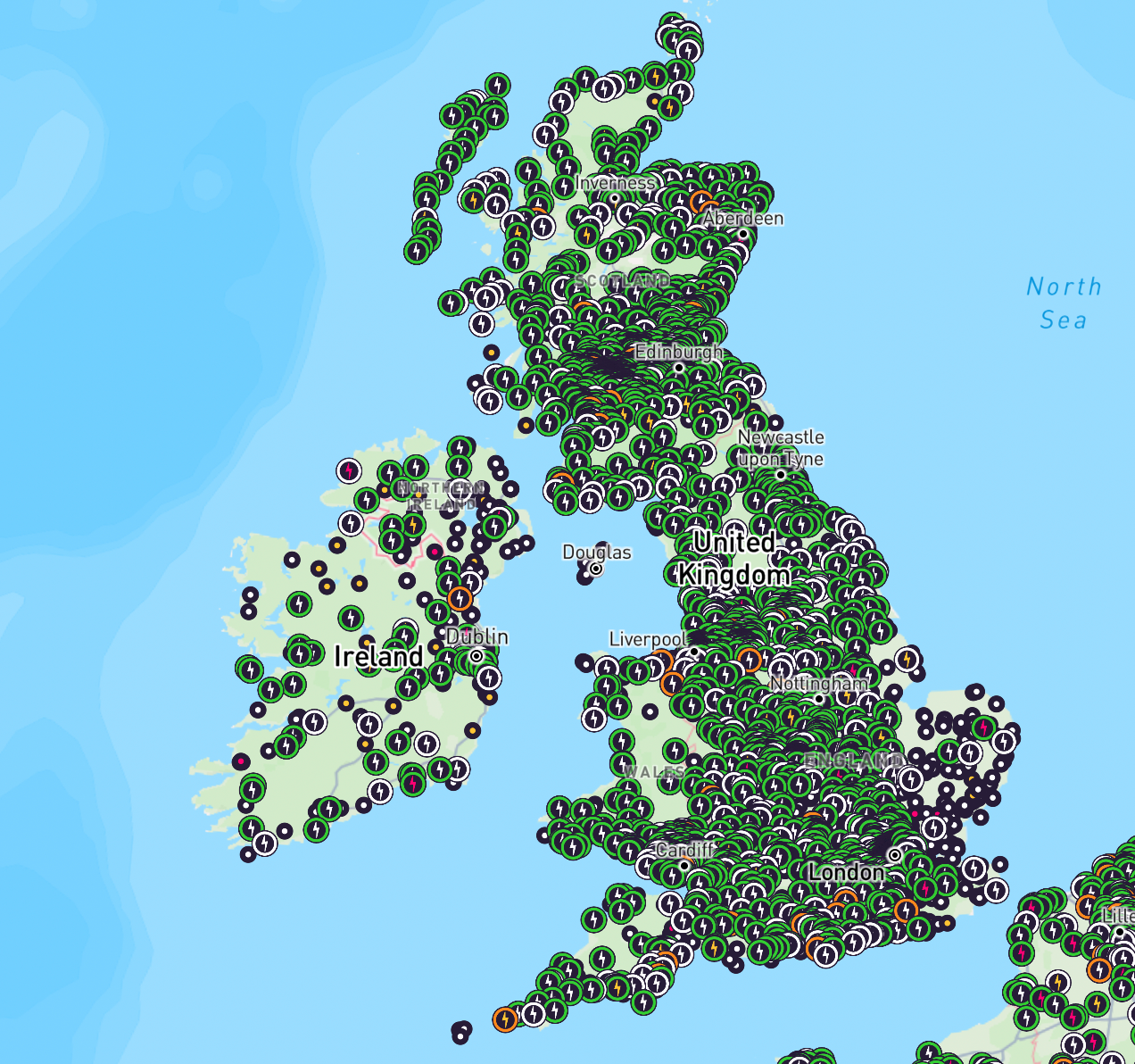

The second is that I live in the UK’s biggest city and there are thousands of public chargers here. And everywhere we’ve travelled so far has had ample charging too. I’m conscious that this ubiquity might not be universal – but… I think if London had even two thirds of the chargers it has now, it still wouldn’t be an issue. Plus take a look at this screenshot from the Electroverse, a charger network from Octopus Energy:

There are chargers absolutely everywhere. And the dots that are green on this map mean they’re available right now. So not only is there plenty of chargers, but there’s plenty of capacity right now.

So even though there's tonnes of chargers and my car has a decent range so many of my friends and family have questioned just how viable it is to have bought this car.

For many, it still feels too risky

I think it’s fear-fulled inertia. Consumers, I think, perceive the personal risks as too high, so they don’t even entertain the possibility of considering an electric vehicle.

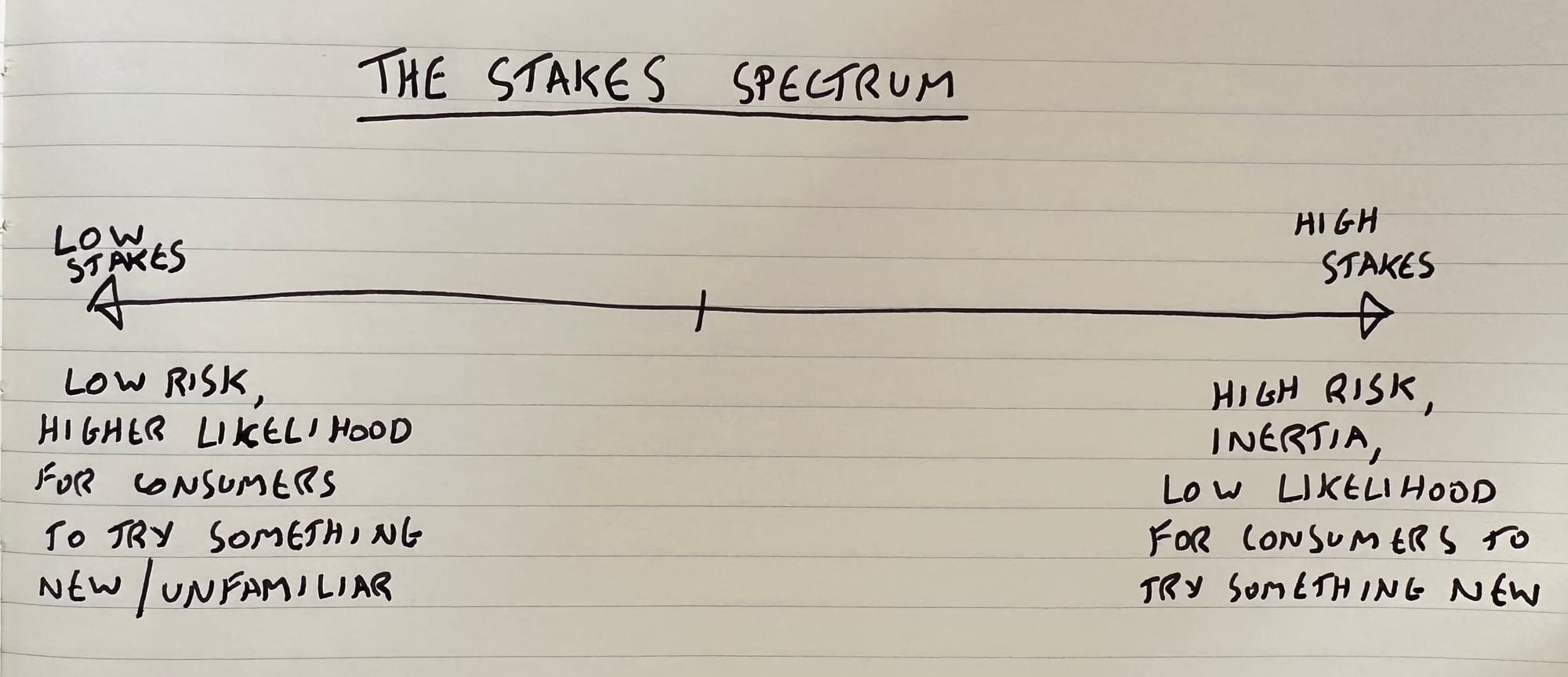

I’ve spent most of my career so far on exactly this problem, in a different context: finance and banking. There’s an invisible line in people’s lives which divides the stakes when it comes to trying new products or services.

On the low-stakes side, customers are willing to try new things. It’s why apps were such a revolution when they were introduced to the iPhone in 2008 – they were low-stakes, fun things people could try on their phones in a controlled environment. Nothing bad was going to happen to your phone: Apple promised it’d review every app, so you’re free to try whatever you’d like.

It’s also why people without severe allergies are willing to try new bars or restaurants – because the stakes are low. The worst thing to happen is a bad meal, and potentially food poisoning if it’s really bad. Not earth-shattering stuff.

Low-stakes categories have easy and free movement between products and brands. It’s how I fell in love with Tony’s Chocolonely – I was a Cadbury’s loyalist, but my world would not have ended if I tried out a Tony’s once. Now when I’m in the mood for a chocolatey treat, I pick up a Tony’s because I took a chance on a new brand, and it was better.

On the other end of the stakes spectrum is banking. Human beings are incredibly protective and primal over their hard-earned cash. They may be tempted by crypto or a flashy new app-based bank, but there’s something ineffably trustworthy about a physical, bricks-and-mortar building folks can go to if anything goes wrong. And this is why incumbent banks haven’t – and won’t – collapse under pressure from Monzo or Revolut, because there’ll always be a fear of things going wrong, and a critical mass of people who take that fear seriously enough that they’ll want a physical place to go if it does.

Much of my time at Monzo was spent on the stakes spectrum, and the strange tension consumers felt about the brand. Is it an app? Or is it a bank?

We could convince millions of people to download the app, but it was a much harder job get them to trust us as their main bank because we weren't doing things the way they has always been done (banking via three-hundred-year-old branch-based institutions vs doing it all in an app).

When Monzo was perceived as an "app", people downloaded it to try and loved it. But the "bank" bit was harder for many customers – we needed to prove to them over a long period of time, and with thoughtful product and design decisions, that we were as trustworthy as Lloyds or Barclays.

This is what I call the stakes-spectrum. On the low end, consumers are willing to try almost anything if the perceived personal risk is low. On the other, consumers are incredibly reluctant to try anything new or unfamiliar if the perceived personal risk is high.

The reactions I’ve had from friends and family when I’ve told them about our new electric car taught me that driving has similar dynamics as banking, I think. That is, that the potential for downside is way more present in folks’ minds than the potential upside. It’s high on the stakes spectrum because people are thinking about avoiding risk rather than getting reward.

The rationalisation for many: the incumbent way is better, because at least I know how that works.

I think there are four ways this electric car inertia can be beaten.

Here’s how.

Create a car optimised for word of mouth

The best marketing is word of mouth, because it’s free. And the best way to drive word of mouth is to create an excellent, polished product that is worthy of telling your friends or family about. Car companies should obsess over creating incredible and different experiences for electric cars, so that early adopters are willing to try it and then willing to talk about the thing they tried.

To Elon Musk’s credit, this was exactly the early Tesla strategy. Create a great car, period. The fact that it’s electric is secondary; the first priority should be that it’s a joy to drive and experience.

As Teslas become riddled with problems, both with car quality and its CEO – car companies should adopt this strategy en-masse. Create a great, novel, different car that just so happens to be electric. Western companies have struggled here; but Chinese manufacturers are proving it works.

It sounds hilariously simplistic to say make a good product, but it’s harder to do in practice than it is to say in theory. Electric car makers should focus on excellent execution, and optimise for Net Promoter Score (a measure of how likely your customers are to recommend your product or service).

Trusted, recognisable brands should throw their weight behind electric

Brands like Volkswagen, BMW, Mercedes and Ford have spent decades building brand equity. They’re well-loved, well-trusted brands. Yet much of their marketing still revolves around traditional cars and they’re leaning back on the safe associations of past products, even as they tackle the challenge of needing to be selling 100% emission-free cars by 2035.

Volkswagen, I think, are the best at this at the moment. They’re the most established brand that have pushed the hardest in marketing and branding their electric offerings – the ID range is distinct enough, and mixing the iconic Golf and Transporter brands with electric to create the eGolf and eTransporter is slowly changing minds.

But these established brands need to be bolder. Electric cars have to be the future if we’re going to save the planet, so they should reorient their brand strategies as such. Put electric at the centre. Ditch marketing for petrol.

Consumer behaviour follows brand messaging, especially if that messaging is from a trusted brand. Should Volkswagen be bold and become an electric-first company, they may well take a short-term hit, but it’d position them wonderfully for a long-term advantage.

A new brand or a category entrant

That behaves a little differently to Tesla.

Tesla, a new market entrant themselves, saw their goal as category creation via excellent product. And they achieved it – Tesla and electric cars are synonymous for many, and the electric car category has been hugely expanded by Tesla’s success.

But this isn’t a zero-sum game – many brands can succeed in creating great car companies and they can coexist. Although Tesla is a strong brand, I think there’s space for a more brand-led strategy to win through for either a new brand entirely, or a new market entrant with already-established equity from another category.

Let’s talk about the latter first – in China, Xiaomi, known primarily as a smartphone manufacturer, has done exactly this. They expect to sell 100,000 electric cars by the end of the year – a huge number for a company known only for tech. We’ve seen less success along these lines in the West – Apple, who were going to enter the car category have pulled out after 10 years of development and billions of dollars spent. A shame – as I think Apple’s brand halo would have propelled the case forward.

There’s space for a brand-new entrant, too. Where legacy car companies are wary of leaning fully into electric cars, a new entrant would not be burdened by history. They would have permission to push the positive case for electric cars in brand advertising – they could even be antagonistic and provocative against the incumbents.

A new entrant to the market could authentically and boldly make the case that electric cars are better than petrol cars in real use, where existing car brands haven't yet shaken the feeling that electric cars are slightly worse versions of their petrol counterparts.

Flip the barriers, tell the world

Any advertising or marketing messaging I’ve seen so far has tried to convince the viewer or reader that an electric car isn’t really that much different to a petrol or diesel car. And I get how we’ve ended up here – car manufacturers don’t want to talk down their petrol cars.

I also think car manufacturers are a little scared to point out the differences between electric cars and petrol cars. They want consumers to feel like they’re not much different from petrol cars. So they design them and market them to feel the same.

But this is the wrong approach and it assumes consumers aren’t as smart as they are. Especially when it comes to buying a car – because it’s a bit expense, it’s a high-consideration, lots-of-research type decision.

Instead, car brands should lean in to the differences between petrol and electric cars. Flip the script here: rather than “you have to plug it in for hours”, the narrative should be “always have a full tank”. Hear me out on this one – because the practical effect is enormous. With a petrol car, you have to seek out a petrol station every now and then. With a petrol car, you have a "petrol station" at home. Plug in when you get home and you’ve always got a full tank the next time you go for a drive.

In London, Manchester and most other bigger cities in the UK, most residential streets have public chargers. Car brands need to lean into this, not lean away from it. There’s a petrol station on every road. Surely this is so much better than visiting a petrol station when you get low?

Inertia and the stakes spectrum

I guess I didn’t realise just how much inertia had been baked into our culture when it comes to cars. People are resistant to change, especially if they’ve heard that that change means their car might become less reliable. Or they might have to change their fuel habits (no more petrols stations, but more plugging in) – and they’re just not willing to spend the mental energy on what this means for them.

But this is the very point of marketing. To move consumers through the marketing funnel. To make them aware of your offering, help them through the barriers and make it super easy for them to buy.

It’s clear that with electric cars it’s this consideration stage: the overcoming of barriers, that is the big problem. It’s time to change that – by flipping the script and owning, proudly, the perceived drawbacks as benefits. And it’s time brands fully embraced electric – reorienting their marketing, product and design strategies around them. Creating great experiences that happen to be electric.

And I think it can be done: both by heritage brands like Volkwagen who can lend trust to these unfamiliar products, or by a new, bold, brave brand that over-invests in share of voice over the coming years and changes the conversation.